Market Review: April 2008 commentary

In this months' Tyndall comment Peter Lynn goes back-to-basics, reviewing all the influences on both our domestic and global markets, and provide some hypotheses of what to expect in these turbulent markets.

Monday, April 7th 2008, 1:42PM

A Volatile Market ExplainedWe are experiencing historic times for the financial markets. Every time we open a newspaper, the headlines are screaming about the latest woes to befall investors.

Credit crunch. Liquidity crunch. Recession. Depression. Inflation. Deflation. Bear market. Bear Stearns. What do all these things mean? More importantly, what do all the various goings-on mean for your investments?

In this month's commentary we will go back to basics and review all the various behaviours that the markets are currently experiencing. To provide some context, we will separate the explanations into its effects on each of the various asset classes as well as that of the overall economy. In all cases we will look at both New Zealand and global influences.

Global Economy

For the past few years, the global economy has been experiencing a "credit boom". This has been a period where borrowing conditions for everyone (businesses and consumers alike) have become very easy and cheap. The main reason for this was the low interest rate environment that persisted around the world since the last major downturn in equity markets in 2001-2002 (which was further impacted by the events of September 11). Finance companies were falling over themselves to offer as much credit to anyone who wanted to borrow it. As a result, lots of money was being borrowed and thus spent, helping GDP growth figures. Finance companies started to come up with new ways of offering "high quality" investments, by pooling together supposedly uncorrelated pools of lower quality borrowings. In this way, they could keep extending credit to investors to keep the boom alive.

The increased spending and growth, though, resulted in some slightly higher prices and a vague threat of inflation reared its ugly head. In addition, China started to emerge as a serious economy and also started increasing the prices of the many goods they exported, or "exporting their inflation". The US Federal Reserve decided to try to contain this by increasing interest rates, but did it in such a gradual, consistent and expected manner that markets barely reacted to short term interest rates going from 1% to 5.25% in three years.

Then, in the first half of 2007, the US property market, which had been becoming more and more expensive over the '00s, started to slow down significantly. Some borrowers of lower credit quality (dubbed "subprime"), who had had no problems acquiring mortgages without any documentation or, indeed, jobs, could no longer afford to service those mortgages and properties were foreclosed as a result.

The investment products that had been built up from the pools of such subprime loans started to show they were anything but uncorrelated and performed very poorly. A number of these complex vehicles were based on mathematical models that were no longer working and they started to unravel rapidly.

At the same time, lenders significantly tightened their loan conditions and it became much harder and more expensive to borrow money. This is what is called a credit crunch. What no-one anticipated, even in late 2007, was how deep this US credit crunch would be and, three months into 2008, the crunch seems to be still deepening as we witness America's fifth largest bank, Bear Stearns, bailed out last month by JP Morgan and the US Fed.

With little credit being supplied to both households and corporates, many of the large economies of the world are in, or very close to, a recession. A recession is defined as two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth and the US is almost certainly in the middle of this now. Japan is either in a recession, or very close to it and there are emerging signs that the UK could be moving towards one as well.

A Goldman Sachs report estimates that the total credit losses will reach USD1.2 trillion globally. So far, US financial firms have written down approximately USD120 billion, which is about a quarter of the expected total that they alone will eventually have to suffer from this crisis. We are clearly still a long way from the end of this.

New Zealand Economy

The New Zealand economy has also been in a boom over the past few years, helped along by a strong property market and significant mortgage borrowing. However, our credit system is very much foreign-influenced, as most of the banks are Australian-owned. Fortunately, despite what has been happening in the US, Australian banks have still been able to borrow significant amounts of capital (but at much higher cost), which has meant that the US credit crunch has not impacted materially on Australia or New Zealand. However, over the last few months there have been signs that it is getting more expensive to borrow money – we have now witnessed banks increasing mortgage rates without a corresponding rise in the Official Cash Rate (OCR).

Of more concern, though, is the start of a significant slowdown in the New Zealand economy. Consumer confidence figures are now at a 10-year low, meaning that consumer spending is likely to be severely constrained. So, will the RBNZ now look at lowering interest rates? Probably not in the near term.

Unemployment is at a 33-year low, while the terms of trade are at a 21-year high. As a result, inflation still has the potential of exceeding its target band, so it seems unlikely that the RBNZ will look at dropping the OCR until much later in the year, if not until some time in 2009.

It is likely that, as well as being more expensive to borrow money, the supply of capital will become more scarce. The foreign capital that has been propping up New Zealand may well be repatriated to prop up the domestic economies of the providers. With an outflow of capital, this will start to reduce the very high Kiwi dollar (NZD). This would be exacerbated with a slowdown in the economy and result in an even sharper fall in the NZD.

However, a falling NZD has the potential to keep inflation high. If the New Zealand economy falls towards recession, then we would be in the high inflation/low growth scenario known as stagflation (which is what we experienced in the 1970s with the oil price shocks).

With this economic backdrop, how do the asset classes stack up?

Global Equities

Global equities perform best when growth is strong around the world and/or interest rates are low and capital is easily available (making it inexpensive and easy for companies and consumers to borrow to invest and spend). Unfortunately, the poor credit conditions in the US are spreading around the world and even starting to impact on the emerging markets. This is exacerbating the effect of a slowdown in global growth.

These conditions make it tough for global equities. While some central banks, particularly the US Federal Reserve have been reducing interest rates, the US credit crunch has been so deep that rates will have to fall much further to have a positive effect on global equities. Currently, the US Fed Funds rate has been reduced to 2.25%, but it may have to fall back down to 1%-1.25% to start to encourage stronger returns from global equities again.

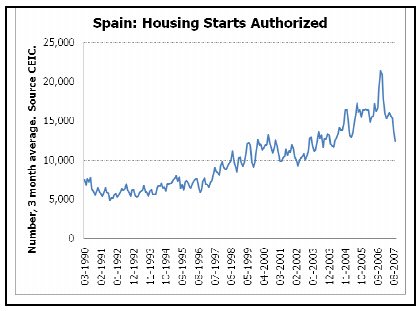

However, as we know, the performance of global equities does not move in a straight line. Within an increasing or decreasing trend, there are a number of rises and falls. So, while the trend over the 2008 year may be one of a deterioration, the fact is that in the first three months of the year, markets have already fallen by over 12.5% on a global basis, or by more than 17.5% if North America is excluded. Currently, most commentators and market "experts" are predicting bleak near-term futures for the global equity markets. It is, though, usually at these times, when bargains abound and the markets engage in a limited (and often temporary) form of recovery. Thus, a strong stockpicker may make some outsized relative returns in this environment and gain an overall return over the next three months that is in stark contrast to what has been earned in the first three months. (We should note that banks and financial services companies will likely continue to write off exposures to various mortgage markets. In particular, the Spanish mortgage market looks in a very poor state and this could be the first of a number of European markets that will hurt those with exposures to them).

The same scenario could be repeated in the second six months of 2008. That is, the first three months could be relatively muted as a global slowdown intensifies (and we see a retreat from the temporary Q2 rally as hypothesized above), while the final quarter may see some recovery as interest rates globally are pushed much lower than where they are today. The liquidity that the latter action would add to the markets would help companies and hence returns.

New Zealand Equities

The New Zealand sharemarket is a small and relatively illiquid market that operates on the margins of the world's sharemarkets. Hence it is highly dependent on capital flows from foreign investors. It is also, of course, very dependent on the New Zealand economy, particularly consumer demand.

The expected New Zealand economic slowdown will certainly have an impact on New Zealand companies. Of particular concern is the consumer confidence slowdown, which will likely see retail sales soften significantly and hence see diminished prospects for companies.

In addition, the continuing high NZD will have detrimental effects on exporters. Exporters would also be severely impacted by the US recession and any recessionary signs from Europe.

A late 2008 rate cut by the RBNZ could provide a good end-of-year boost for the New Zealand sharemarket, but it is likely that over the course of this year, the New Zealand market will react broadly in line with global markets, although on a somewhat more muted scale.

There is no question that the market as a whole is far from the expensive levels it was in 2007. Since the peak in early October 2007, the market has fallen by over 20%, with over 15% of that fall occurring in 2008.

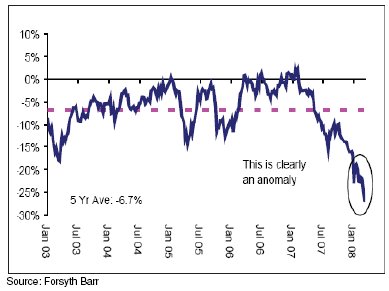

Forsyth Barr research believes that the market is trading at a 23% discount to fair value, which is the deepest discount in the past five years. (See Price to Valuation History chart below.)

What this probably means is that, notwithstanding the comments above regarding the impact of a continuing high NZD and a slowing New Zealand economy, there are probably a number of bargains out there in the New Zealand stock market.

These will be companies with strong fundamentals that can withstand the environment over the course of the rest of 2008. A history of providing good earnings growth would also be an indicator of a company whose stock may increase in value over the next few quarters.

Global Bonds

The global bond markets have been an interesting place, particularly as debt instruments have been at the heart of the problems now engulfing the financial world. On the one hand, we have government bonds, which have been performing very strongly due to their safe haven nature and the fact that interest rates have started falling around the world. In fact, as global growth slows down, US Treasuries and their like will likely continue to rally further. With expectations that there is still a long way for interest rates to fall, it seems that the future is very rosy for government bonds.

On the other hand, is the rest of the global bond universe. This includes corporate debt, asset-backed securities, mortgage-backed securities and structured products. The main problem with all of these instruments is that their spreads over government bonds have widened over the past six to nine months, as market participants have generally reconsidered their appetite for risk. This widening has been on an enormous scale – in fact, spreads have blown out to around five or six times their former level. One of the contributors to the reduction in their values is the indexes that have been created by Market and the like. With hedge funds able to short these indexes, this has placed further pressure on already beaten up securities.

Some of these spreads have become so wide that their underlying securities are now becoming relatively cheap. For example, AAA CMBS securities are now cheaper than BBB corporate debt. Corporate debt is also very cheap, especially for banks and financial service companies. As we have seen in the UK with Northern Rock, governments are reluctant to let banks fall over, so at some stage debt issued by quality banks will make extremely attractive purchases.

However, there is still a great deal of uncertainty in the markets and uncertainty breeds volatility. Non-government bond markets do not like volatility, so there is the potential for these securities to become even cheaper over the next month or so.

Overall, the prospects for global bonds looks good for the remainder of 2008. Government bonds look set to continue their rally and, at some stage, there will be a strong turnaround in the performance of the non-government securities as well.

New Zealand Bonds

One of the problems with New Zealand bonds as an asset class is that fund managers are normally benchmarked against the New Zealand Government Stock Index. This index is made up of only seven Government issues. As a result, most New Zealand bond portfolio managers have a portfolio that has a number of credit issues as well.

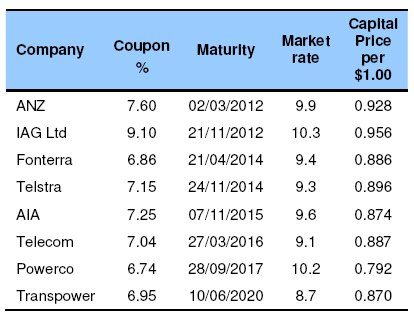

Just like in global credit markets, New Zealand credits have underperformed as spreads have widened. As these bonds are all marked to market, they have underperformed relative to the Government Stock Index. Those with longer duration (or average time to maturity) are more affected the wider credit spreads are.

Some examples of the impact the credit widening has had on corporate bonds last month can be seen in the table below. We expect all of these companies to continue to meet their obligations to bondholders and repay 100% of principal at maturity. Note, though, the large reductions in their capital prices.

Another example of this are bonds organised by ABN Amro, which are linked to credit indexes and issued with a AAA rating. However, in late February they were de-rated to BBB+ as the credit indexes performed poorly in light of the volatility. Corporate bonds in the global credit indexes have an average rating of around A and are refreshed every six months (so credits that fall below investment grade are removed from the index). These structured bonds are expected to pay out in full at maturity. Therefore a deterioration in price should be only a temporary phenomenon.

Of course, the cheapness of these stocks means that buying opportunities abound. When markets become more liquid, these opportunities should present themselves and offer good opportunities for this asset class. However, this may be some time off. Australasian banks have been in a good space relative to their foreign counterparts over the past few months. The signs, though, are now that there will be higher loss provisions going forward as the slowdown impacts a larger number of the banks' customers.

Another phenomenon in the New Zealand fixed interest market is that money market rates have been higher than bond yields for a few years. Short-term interest rates are now at the top of their cycle. If the economy moves close to recession, we could see rate cuts, so that bonds issued by well rated corporates with yields in excess of 9% will look attractive.

A 'normal' sloped yield curve may be a few months away, so cash will probably continue to be the best-performing domestic fixed income asset for the next three to six months on a risk to reward basis. However, bond portfolios should continue to be held. The high cash rates will eventually fall and bonds will reward the investor again.

Overall

The different scenarios and hypotheses mean that holding a balanced portfolio is still the best strategy to ride through turbulent market environments and capture upside benefits when markets recover. One difficulty at the moment is that there is not a great appetite for buying, so it is very difficult to sell securities at present, without significantly discounting the price. Hence the best position to take is to hold tight until liquidity returns to the markets.

The markets will likely continue to be volatile over the next six months (although there may be good periods within this). There is a potential for furthering lowering of interest rates that could see rallies in both bonds and equities later in the year.

Peter Lynn, CFA, Head of Strategy

The global slow down has begun

The global economy has begun to slow, potentially quite sharply. Unsurprisingly, given the problems now affecting the credit system, the US economy has probably already entered a recession. For many years, the US private sector has operated on a cash flow negative basis, always needing to supplement its level of income through borrowing in order to fund its existing level of expenditure. But, now that the supply of credit has become restricted, both companies and households have become obliged to spend less. Hence, we expect that the economy's growth rate has turned negative and we further suspect that the UK, which in many ways resembles the US economy, has also begun to feel the effects of the credit market debacle. Canada, too, is also showing some signs of an adverse reaction to the events within the credit markets, although it seems destined to be less severely affected. However, it is not only these economies that have been affected by the recent change in financial market conditions.

The problems within the international credit markets have also led to a reduction in the volume of funds flowing within the Euro Area. Previously, Spanish, Portuguese, Greek, Irish and even Italian banks had been able to draw on the surplus funds within Germany and others' relatively soft economies and then use these funds to finance extremely aggressive lending campaigns in their local property markets. Unfortunately, these property booms became so intense over recent years that they led the local populations to demand higher wage awards, so that the residents could afford the rapidly inflating house prices. Consequently, these countries, through a mixture of wage and property price inflation, have become fundamentally uncompetitive within the context of the Euro Area. However, now that the credit flows have been reduced, the property booms have each ended and this has exerted a very significant headwind for the domestic household sector's ability to expand its level of expenditure. In fact, most of these countries are now both suffering weaker domestic demand and the effects of their fundamental lack of competitiveness, a situation that itself has recently been made worse by the strength of the Euro on the foreign exchanges.

Consequently, we regard it as highly unlikely that the Euro Area will provide an "oasis" of growth in the current environment. Instead, it seems that with Germany still relatively weak and other parts of the system suffering from an unhealthy combination of weaker domestic demand and poor competitiveness (within the context of a weakening world trade environment), the risks to Euro Zone growth remain firmly on the downside.

Moving eastward, we find even more cause for concern. During the peak of the global capital flows boom between 2003 and mid 2007, many of the former Eastern Bloc and Soviet republics borrowed very aggressively in foreign currencies in order to fund their own rampant housing booms, strong domestic consumption spending growth and widening current account and trade deficits. Now, as global risk appetite wanes and the capital flows subside, not only is the financing for the domestic booms dwindling, so too has the financing for the current account deficits. As a result, their currencies are under pressure and some of the central banks are being obliged to defend their exchange rates through higher interest rates, or face sharp falls in their currencies that could bring instant insolvency to the many households and institutions that have borrowed abroad. In such an environment, financial crisis and economic recessions are fostered. We would also note that South Africa is also facing a similar challenging situation, as is Iceland.

In Latin America and indeed in Australasia, the countries have naturally benefited from the recent upward trend in the prices of many of the commodities that these areas produce (a trend that seems to have been exaggerated by high levels of speculation in some cases). The terms of trade improvements implied by these higher prices have of course provided a boost to the economies but we find in many cases, and particularly in Brazil, Australia and New Zealand, that the commodity price boom has been mortgaged many times over through the aggressive borrowing from international capital markets that has occurred. While it is natural that people receiving higher prices for their (commodity) output should want to spend more, it seems that the populations of these countries have taken this reaction to an extreme, supplementing their income gains by recourse to substantial and consistent borrowings. Hence, these countries each possess strong rates of credit growth and large current account deficits that have arisen as a result of the strength of domestic spending - and despite their increased commodity wealth. But, with the international capital flows that funded this 'extra' borrowing now at risk, and local funding costs rising, the credit booms and hence the economic booms in these regions are also at risk in the current environment. Indeed, in the case of New Zealand, we may already have seen the first signs of an approaching significant economic slowdown and we suspect that Australia will soon see some signs of an economic slowdown.

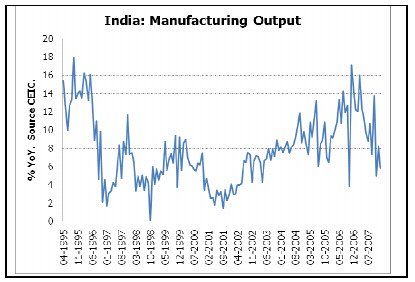

In Japan, the combination of a weakening global environment, a still convalescent domestic credit system and a sharp tightening of the government's fiscal position has probably already delivered a recessionary situation and as yet there has been little or no policy response to this outcome. Elsewhere in Asia, we find that contrary to popular belief, India's economy has already seen its rate of growth moderate following last year's move to a tighter monetary regime and a modest slowdown in its rate of export growth, while China's economy is also now showing signs of having reached a peak. Indeed, China's growth / inflation mix has recently deteriorated quite substantially following not only a reduction in capital inflows but also a rise in nominal wage inflation rates and a potential decline in export growth caused by the problems now afflicting many of China's trading partners. In addition, Korea's economy has also shown some recent signs of softness, as has Taiwan's. The Asian Region clearly does not face a repeat of its 1997 Crisis (that fate may befall Eastern Europe), but growth rates are clearly moderating.

Thus, it would appear that the outlook for world growth is not an attractive one at present. Moreover, that fact that this growth is being led by a credit slowdown, which will imply that people will have to save more on average, does not bode well for corporate profitability. When people save rather than spend, corporate revenues will tend to decline relative to wage bills, with the result that profit margins become depressed at a time during which sales growth can be lacklustre. Hence, the near term outlook for equities remains one of uncertainty, although in the near term, a technical rally may be due.

Naturally, as global growth subsides and inflation worries abate (a process that has already begun in the US, UK and elsewhere), more central banks will begin follow to the US Federal Reserve not only into reducing interest rates, but also into utilising more inventive 'quantitative measures' in an effort to resuscitate their economies. Indeed, by the second half of the year, we would not only expect interest rates will be falling globally – including in the Euro Zone – but that many of the central banks will also be offering collateral injections to the troubled investment banking community which lies at the centre of the current credit market storm (as Bear Stearns recently proved). Since these collateral injections into the investment banks are likely to take the form of 'loans' of government bonds (which the investment banks can then offer as collateral to their creditors), we believe that the central banks will first have to become significant buyers of government bonds (so that they can lend them) and it is for this reason, coupled with the prospects for lower short term interest rates, that leads us to assume that global bond markets may rally further in the near term, despite their already rich valuations.

Finally, with regard to the outlook for the currency markets, we would suggest that with both the credit market debacle and its implications for growth now 'going global', some of the pressure on the hitherto beleaguered US dollar may be reduced. Indeed, although we expect the Yen to remain strong as result of its huge trade surplus, we suspect that the signs of weaker growth in Europe and Asia will tend to place some downward pressure on these area's currencies. Meanwhile, the weaker global outlook may also begin to cap and perhaps reverse some of the commodity currencies, such as the Australian and New Zealand dollars.

Andrew Hunt, Andrew Hunt Economics, London

| « ASSET - Thoughts for the day | ASSET - NZ's boutique renaissance » |

Special Offers

Commenting is closed

| Printable version | Email to a friend |