Market Review: September 2008 Commentary

Around the world, economies are coming down to earth. Rapidly, and with a bump. In these times of poor, often negative investment returns, Peter Lynn comments on KiwiSaver.

Tuesday, September 9th 2008, 1:26PM

Negative returns early in a regular contribution investment, is not the worst thing. Most important though, is choosing assets relevant to your investment time horizon. Yes, another “down to earth” comment!Here’s an easy starter for 10. If you were offered three KiwiSaver funds whose returns over the next 20 years were going to be:

- A. 6.0% p.a.

- B. 12.4% p.a.

- C. 7.0% p.a.

Which fund would you choose? OK, the answer’s obvious, right? You would choose fund B. Certainly if you were a single lump sum investor (say, a child), then B is the correct choice. But what if you were an employee, regularly committing a portion of your (hopefully growing) salary/wages? The correct answer then becomes that dreaded multi-choice option D: There is not enough information to answer the question.

Actually, if you had all the information that I had in selecting those three numbers above, the correct answer is A. Seriously. You see, the three numbers above represent actual gross returns from the New Zealand sharemarket over different 20-year periods: A is for the 20-year period starting on 1 October 1987 (just before the crash and exactly 20 years prior to the actual first KiwiSaver monies getting invested), B. is for the 20-year period five years prior to A, and C is for the 20-years ended 30 June 2008.

Now, if you contributed $100 a month at the start of each period (and the Government did the same) and your monthly contributions grew at 4% p.a. (representing wage inflation), these are the total values you would have accrued (ignoring tax and fees) at the end of each 20-year period:

- A. $210,400

- B. $152,436

- C. $149,338

So, although A had an investment return less than half that of B, it generated an extra $60,000, or nearly a 40% higher outcome. C was relatively close to B’s outcome, despite only earning 56% of B’s return. How on earth can this happen?

The answer lies in the pattern of returns achieved. In particular, it is the instance of large negative or positive returns and the accrued quantum to which that return is applied. For example, if you suffer a 10% return when you accrual has only reached $10,000, you will lose $1,000. If, however, your accrual had reached $100,000 and you suffered a 10% return, you would lose $10,000 and subsequently be worse off, all other things being equal.

Hence, it is far better to have more negative returns at the start of a period of regular investment than towards the end. This is exactly why those with longer time horizons can take on more volatility than those who need the money soon.

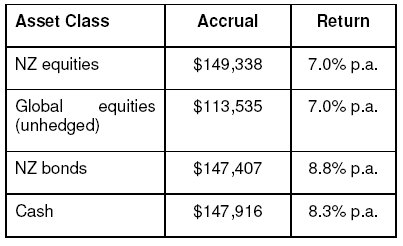

Just for interest’s sake, I have compared the result for C above (a contribution of $200 a month increasing by 4% p.a. into New Zealand equities for the 20 years ended June 2008) with some other asset classes (using the standard market indexes) over the same time period. The table below provides the accrued values (again ignoring tax and fees).

Again, return differentials bear no relation to the order in which the accrued values end up. Given the influence large negative returns have on depleting accrued values, you could be forgiven for assuming that cash’s steady always-positive returns offer a far better proposition. It does, but only in the final years before you actually need that accrued value. Over time, cash will usually not accrue as much as growth assets. For example, if our 20-year period was moved back nine months, cash and bonds give similar amounts as in the table above, whereas domestic shares provides result A. above, over $60,000 more.

So, what is the moral of all this? One take-out is that negative returns are not the worst thing you can get in the early years of a regularly contributing investment (such as KiwiSaver for employees). In the same way that people who fill up their car with petrol once a week are now rejoicing that petrol prices are falling (hence each dollar buys more petrol), a regular contribution into a falling investment buys more units of the particular PIE you are investing in. As long as you don’t need that nest egg in the near future, then there is plenty of time for the investment to grow in the future.

In the same way, do not be dismayed if your particular KiwiSaver fund has not performed as well as others in the various performance surveys that will undoubtedly come out over the next few months. As shown earlier, the actual investment returns earned over a period of time may not have particular relevance to the total dollar outcome you will receive at the end of a regular investment schedule.

Finally, if you do need a lump sum at any stage in the near future, whether for retirement, emigration, house purchase, whatever, it then becomes relatively important to move it towards less volatile assets as that date approaches. Incurring a large negative return just prior to needing this money can leave you with a lot less than you expected, with no time to recover this.

Peter Lynn, CFA, Head of Strategy

To see this month Market Review numbers click here

| « ASSET: FAB finale - Last moves for advisers | Market Review: September 2008 London Commentary » |

Special Offers

Commenting is closed

| Printable version | Email to a friend |