Market Review: London October 2008 Commentary

Time for thrift, saving and avoiding further debt, at both a corporate and household level seems to be the theme, if it is not too late for some. Andrew Hunt gives us the global view from his recent US visit and his assessment of the ‘bailout’ package, if the House votes ‘aye’ on Saturday (NZ time).

Tuesday, October 7th 2008, 9:37AM

There is an Irish ‘rural myth’ about the tourist who stops at a pub to ask directions to Dublin, only to be told “that if I wanted to get there, I would not start here”. It is perhaps a shame that the US Congress had not heard that story. If the US economy was to achieve an optimal, free market, equilibrium with long term economic stability, then it should not have been allowed to embark on a series of credit booms from the mid 1980s onward.

But, the fact remains that the economy was allowed by the government to experience credit booms between 1986 and 1989, 1992 and 1999, and 2003 until 2007 and it is these booms that led to a fundamental degrading of private sector balance sheets and it is this issue, more than any other, that the US lawmakers had ultimately to address when they met to finally approve the Bush-Paulson bailout plan, a plan that we suspect will prove simply to have been merely the second instalment in a long running saga.

Although they may have appeared to bail out Wall Street’s ‘fat cats’, they were simply enacting one of the measures that the US real economy needs if it is to survive its current trials.

Specifically, US consumers are now the most indebted that they have been in the post war period and perhaps ever (the only other contender for the title being 1929).

Unfortunately, this peak in indebtedness has occurred just as house prices have declined and employment prospects have deteriorated, events that suggest that consumers may now wish to repay debts, reduce their gearing ratios and strengthen their balance sheets rather than extend them further. Thus, the usually spendthrift US consumer has begun to save.

Meanwhile, following the long Mergers and Acquisitions Booms, the Private Equity Boom and the trend towards equity retirement, US companies are also the most indebted that they have ever been. Unfortunately, corporate sales revenues have begun to decline as their customers (ie households) have started to save rather than spend.

The natural reaction for companies in this situation is also to ‘save’ by shedding inventories, reducing capital spending and cutting their wage bill. Unfortunately, the corporate sector’s wage bill is also the household sector’s income, and the reduction in income in the household sector has further lessened the latter’s ability to spend, which in turn has implied that corporate receipts have come under further pressure in this vicious cycle which is more formally known as the Paradox of Thrift.

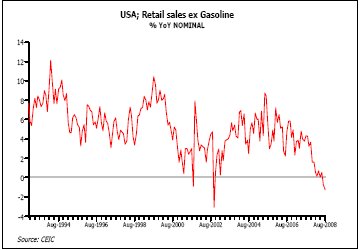

With everyone saving and no one spending, US nominal retail sales growth has turned negative for the first time ever and corporate earnings growth has plummeted accordingly.

We would suggest that the only realistic way in which this Paradox of Thrift cycle can be arrested is if people and companies are essentially ‘given’ cash so that they can discharge their debts without first having to reduce their expenditures relative to their incomes.

Unfortunately, the only feasible entity that can conceivably provide this ‘charity’ is the US government itself and it is for this reason that we believe that the real economy can only be stabilised through massive fiscal injections, such as that which we saw earlier this year, that we are about to see in the latest Plan and that we expect to see again within the next few months.

Naturally, such generous action by the state seems set to lead to wide government budget deficits (we are forecasting a trillion US dollar budget deficit for the US in 2009) that some on Capitol Hill may find hard to stomach, but that we believe offer the only reliable solution to the current crisis gripping the real economy.

With regard to the crisis in the financial sector, which recently at least appears to have displaced the real economic crisis in the newspaper headlines, we believe that determined government action was necessary, whatever the cost to the tax payer.

Eighteen months ago, we embarked on a research effort to better understand the actual mechanics of the US credit boom and we found that following two key events of the late 1990s / early 2000s, the nature of the US credit system had begun to change fundamentally.

The first event was the widely publicised ‘Greenspan Put’ that appeared to offer the promise that the Fed would always bailout speculators and other institutions if they got into serious trouble.

The second key event was the less publicised campaign by New York Attorney-General Spitzer against perceived bad or improper advice provided by investment banks to their clients.

These two events served to make ‘giving advice to clients’ a more dangerous occupation than being a speculator for one’s own account and these two (public sector orchestrated) events persuaded the US investment banking community to transform their businesses from being ‘agents’ of their clients within financial markets to being principals in their own right.

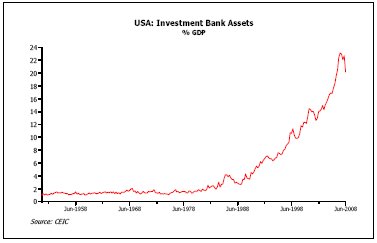

Hence, the 2000s saw a dramatic rise in the size of the balance sheets of these institutions, both in absolute terms and relative to such yardsticks as the level of US GDP.

In fact, by 2007, these institutions had grown their balance sheets to such an extent that their notional on-balance sheet assets were around $3 trillion and their total balance sheets may have been over a hundred times this amount, numbers that made them by far and away the largest investors in the global financial system.

In order to expand their assets, these institutions employed massive gearing ratios (total assets relative to total capital were well over thirty times – ratios that would make aggressive ‘hedge funds’ look like wimps) and the creative use of matrix algebra.

The massive growth in the investment banks’ balance sheets was concentrated in the mortgage bond derivatives sectors and it relied on the use of incredibly complex mathematical models that were nevertheless remarkably reliant on a number of basic and naive assumptions.

In a way, the investment banks’ asset growth resembled a sausage machine. Pieces of ‘unwanted mortgage debt’ were packaged into ‘sausages’ and sold to either investors or, more normally, held by the investment banks as the assets noted above.

Of course, if you actually knew what was in a sausage you would not touch it but considered as a ‘package’ these instruments appeared strangely appetising. Unfortunately, as we now know, these sausages were not even put together well – the mathematical models that had been employed were simply wrong and as every high school student knows, you either get maths right or wrong – there is no ‘a bit wrong’.

As the flaws in the mathematical models have become apparent (to the cognoscenti as early as May 2007 but only to the majority of analysts more recently), the ‘sausages’ have been seen to be almost worthless.

At first sight, there is clearly an incentive to say to the investment banks that it was they who made the mistakes, they who mis-specified the models and they that purchased them, and therefore they should be left to suffer the consequences with no assistance from the state.

But, if the investment banks had been left to suffer the consequences of their actions, the forced deleveraging and asset price falls would likely have bankrupted the entire financial system, destroyed real people’s wealth and encouraged even more saving – and hence an even more aggressive paradox of thrift crisis in the real economy than we are already facing.

In practice, the bailout will not simply be the state giving the banks lots of cash in exchange for near worthless assets. In reality, the bailout will more likely take the form of a de facto asset swap whereby the banks give their bad assets and inflated prices to the state in exchange for Treasury bonds and we suspect that the actual amounts involved will top over $1 trillion, well over the current $700 billion that has so far been agreed.

However, since this is an asset swap rather than a simple cash injection, the package should in some senses be self-financing, providing that the investment banks can afford to hold the Treasuries.

We include the last caveat because at present, the banks’ funding costs are substantially above the yield on Treasury bonds and thus to hold Treasuries at this moment would cost the banks money, rather than help them rebuild their profits and capital.

Therefore, it is imperative that if the package is to work, the Federal Reserve must reduce short term interest rates so that the banks’ funding costs fall below Treasury yields.

If the Fed does not do this, we would fully expect the latest package to fail (with disastrous consequences) but, fortunately, with the global inflation threat fast receding, we see nothing to stop the Fed and other central banks cutting interest rates.

Of course, the launching of so many lifeboats for both the real economy and the financial sector is clearly not an optimal situation but the US is simply not in a position that could be described as optimal – it needs rescuing and while this rescue has costs, the alternative would ultimately involve even larger costs in terms of financial distress, unemployment and recession.

Thus, this may not be the route that the US would like to take, but we suspect that it was the route that it had to take in the circumstances and while these measures may not bring an immediate economic recovery, they will at least save us from a worse outcome and that should bring some cheer to asset markets in the near term.

Andrew Hunt, London

| « Market Review: October 2008 Commentary | Market Review: London November 2008 Commentary » |

Special Offers

Commenting is closed

| Printable version | Email to a friend |