The great Central Bank unwind

Whether by luck or design, when I first entered the world of applied economics during the mid-1980s, I decided that I would like to specialize in covering central banks and in studying the flows that these institutions could create within financial systems and the real economies of the world.

Friday, January 13th 2017, 9:18AM

by Andrew Hunt

Little did I know that over the late 1980s and the 1990s, the central banks would rise in prominence to become arguably the dominant influence on financial markets and this trend has probably only strengthened over the last decade or so – central bank governors are now known even within the popular press. However, it now seems likely that the pendulum of popular opinion and market sentiment is likely to turn against these institutions as they face arguably one of their most difficult years since the late 1970s. Arguably, all of the major central banks are facing a potentially daunting 2017 as some of their past mistakes – or necessary policy compromises – come back to haunt them and as a result we suspect that 2017 will be a most interesting year for investors.

For example, in the USA we find that despite some evidence that in aggregate the US economy is still working at below full capacity and employment, the Federal Reserve of course elected to raise interest rates last month. In reality, we suspect that there were four motives behind the move: to help to improve potential profitability in the banking system (not an objective that they will have wished to advertise but an important and we believe justifiable one nonetheless); to validate the recent upward move in market-determined interest rates; to provide some impediment to the extreme levels of corporate financial engineering and speculation that has been taking place; and finally to give the central bank some two-way optionality on future interest rate moves should circumstances demand. Consequently, we would describe the Fed’s actions as representing a mixture of prudence and opportunism, both of which of course have some merit.

As to the outlook for rates, we continue to believe that the FOMC may be being rather too optimistic over the outlook for the economy: the ‘freak’ rise in soya bean export shipments over the third quarter of 2016 will have created a high comparison period of net trade, thereby making it more difficult for the latter to contribute to headline GDP in the near term. Moreover, we quite naturally expect that net trade foreign trends may also suffer in the near–medium term as a result of the rally in the USD over recent weeks. Net trade trends are also likely to remain at the mercy of global developments, particularly in both Europe and the PRC. Elsewhere within the data, we find that there is some evidence that the Obama Administration indulged in a significant fiscal easing of its own ahead of the elections but this will likely wind down in the near term as the economy waits for the new Administration to “get up and running”, thereby implying that there may well be a fiscal drag rather than tailwind in the near term.

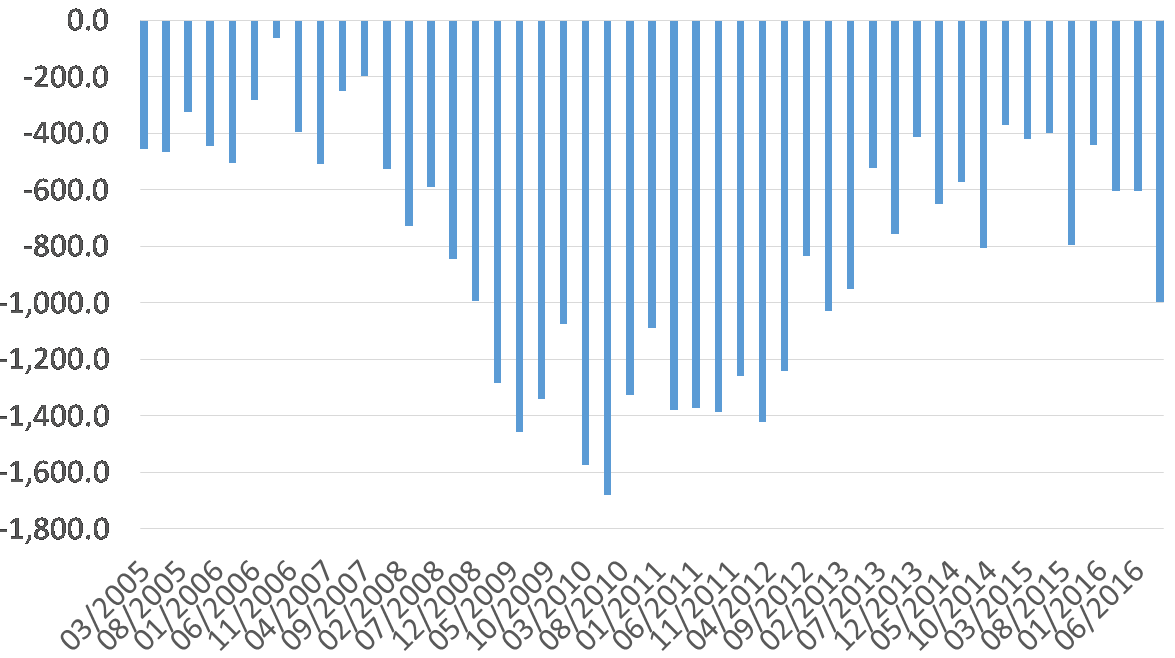

USA: Govt. Financial Balance USD billion

Elsewhere within the US economy, we find that inventory ratios remain high, household real disposable income growth has slowed, the residential construction data remains soft (and mortgage lending trends seem to have weakened since the election). Within the corporate sector, companies remain dis-inclined to invest in new plant and equipment, instead preferring to direct their financial resources at zaitech-type pursuits. With these various but unfortunately numerous headwinds all likely to be in play in early 2017, we are minded to believe that the Federal Reserve’s expectations for growth in the USA in 2017 may again prove to have been too optimistic, even if China and Europe do not create ‘exogenous’ shocks of their own.

Unfortunately, we suspect that both China and Europe will provide their own headwinds to global growth. The author has just returned from a grand tour of European Central Banks (thankfully with no help from Clarkson et al) with the distinct impression that intra-European relations are at a very low ebb currently, particularly within the central banks. Certainly, there seems to be a particularly wide intellectual chasm between North and South at present, with the North complaining that the South needs to do more to improve its competitiveness by encouraging the euphemistically described ‘internal devaluation process’ (= painful deflation, not something that democracies can do in normal circumstances...), while the South says that the North needs to inflate and to behave in a more ‘collective’ fashion. The Bundesbank, however, flatly refuses to do the latter and hence we must remain fundamentally bearish on the EUR’s prospects for survival in its current form.

Moreover, the new tension that is fast emerging within the inner workings is the Euro System revolves around the level of interbank rates. As a result of the political uncertainty in Italy and elsewhere, Europe is once again witnessing large flows of funds out of the banking systems of the South and into the systems of the North – primarily Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. These fund flows are so large that the recipient banks cannot hope to be able to recycle them into new lending into their own economies, in part because there simply is not enough demand for new credit and because the banks are constrained by their weak capital adequacy positions. Hence, the Northern banks end up depositing the surplus funds at their own central banks. However, at present, the interest rate that the Northern banks receive when they deposit their (huge) surplus funds at the central banks is set at minus forty basis points, a situation that implies that the banks are making a loss on almost every Euro that leaves the South and flows to the North. This absurd situation is of course undermining the Northern banks’ profitability and further depleting their capital positions, a wholly counter-productive situation.

In our view, the only practical way to alleviate (not unfortunately solve) this fundamental problem would for the ECB to return interest rates into positive territory. Unfortunately, the obvious problem for the ECB is that if it raises the short term interest rates in order to save the capital positions of the Northern creditor banks, then it will risk creating a bond market crash of epic proportions (given the current level of bond yields and the necessity for investors to expect to make holding gains before they will even buy a bond...) that would likely cause credit spreads within Europe to blow out with a potentially fatal impact on the solvency of the Southern governments. This might also prove fatal to the Union.

In theory, such a potentially calamitous outcome in the debt markets in response to a rate hike might be avoided if the ECB were to adopt a Japanese-type stance by increasing the size of its QE in order to support bond markets, but we doubt that the Bundesbank would have much appetite for such a strategy and, if one were to be enacted, it is probable that the vendors of Italian, Spanish and other bonds would quickly remove the monetary proceeds of their sales from the countries in question, thereby placing yet more pressure on the Northern banking systems..

We would therefore argue that the ECB is effectively caught in a ‘Catch 22’ situation and we suspect that the best that they can hope for is that the Fed (or even at a stretch the BoJ) does their dirty work for them by raising interest rates before them and in so doing ‘stressing bond markets’ even before the ECB moves, if only so that the ECB does not get the blame for what might follow........ Clearly, 2017 is likely to be an immensely challenging year for the ECB and the Euro Zone in general.

On the other side of the World, we suspect that in many ways, the BoJ faces the easiest task of all the major central banks next year. According to our analysis, Japan’s economy has picked up a little momentum of late and overall capacity utilization is either running at trend, or even slightly above trend at present. In such an environment, we can assume that the BoJ has probably little need to do anything at present, although exogenous events might yet leave it looking for some way to react.

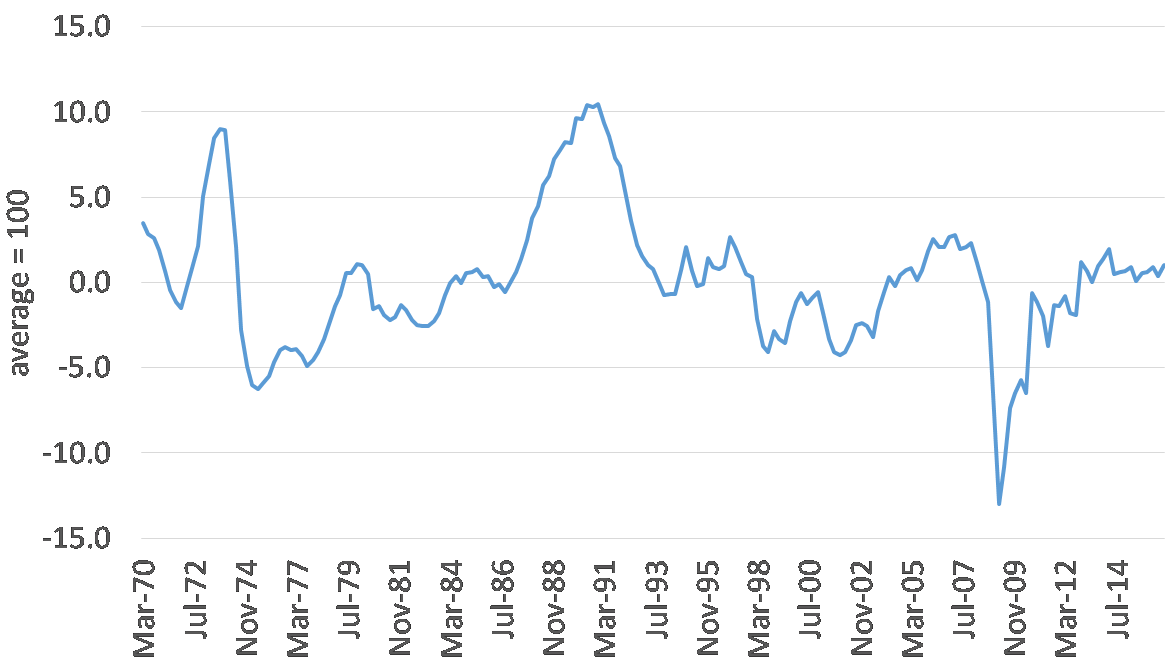

Japan: Demand Pressure Index

If there are not any exogenous shocks (and, unfortunately, we suspect that there will be), we would expect the BoJ to continue to edge towards an eventual tightening within the next few years by continuing its efforts to boost its own capital base. The latter needs to be achieved so that the Bank will be able to ‘afford’ the negative carry on its bond holdings that it will ultimately face when it raises short term interest rates and begins paying interest on the commercial banks’ excess reserves that are held on its balance sheet. For markets, the notion of an inactive BoJ may potentially appear as being somewhat constructive for the yen but, in the first half of 2017, we suspect that sentiment to the JPY will be dominated primarily by events in China, which seem unlikely to be positive.

Certainly, we suspect that 2017 may prove to be a traumatic year for the PBoC. Having presided over a simply immense and almost unprecedented expansion of liquidity within its economy, and as a result witnessed not just a domestic (consumer-driven) recovery but also a renewed deterioration in the country’s long term capital account and its overall balance of payments, the PBoC has recently changed course once again and begun a modest tightening that we suspect will succeed in reducing credit growth in the early part of 2017. Given that the bulk of China’s private sector remains heavily dependent on credit, we can expect any slowdown in credit growth to be reflected relatively quickly in a renewed economic slowdown.

However, such a slowdown is not what concerns us the most when it comes to the outlook for China in 2017. China’s recent imposition of apparently more stringent capital controls can be viewed as in effect closing the pressure relief or safety valve on a steam engine that has been fed too much coal (i.e. money and credit). The result of such a situation is likely to be an ‘explosion’ and in this case, we are referring to a likely explosion in the rate of inflation.

If China’s savers cannot diversify their excess money holdings into foreign assets, then we fear that they will instead seek to acquire yet more domestic property assets. However, as property prices rise, the cost of living and social pressures will rise, thereby placing upward pressure on wages. History suggests that once capital controls are imposed on economies with high excess money balances, the rate of inflation can move higher surprisingly quickly.

It is therefore quite probable that the PBoC will face itself with that central banking nightmare of stagflation before 2017 is finished: the Bank will face pressure to ease in order to support employment but at the same time the higher inflation will invite calls for higher rates. The PBoC Chairman’s lot next year is unlikely to be a happy one.

Ultimately, we suspect that the tighter capital control regime may not prove sustainable and instead the PBoC will be obliged to allow the RMB to decline significantly so that “foreign assets become prohibitively expensive” to China’s savers but any fall in the RMB will also add to the inflationary bias within the domestic economy in the short term (via its impact on import prices) and of course it will invite a protectionist reaction from China’s trading partners in the West, and competitive devaluations from its trade competitors elsewhere within the Region.

In the opening paragraphs, we noted that over the last two or three decades, markets have come to embrace central bankers as being some form of omnipotent beings with the markets’ best interests at heart, a view that reached its peak in the treatment and almost adoration of Alan ‘maestro / the Man that Knew’ Greenspan. However, this view of the world - that Greenspan more than anyone else himself helped to create - may yet be about to face some of its most severe ‘operational challenges’ at a time in which many of the world’s populations have already grown tired of the effects of many of the Central Banks’ existing policy-actions. Therefore, we suspect that sentiment may turn against the Banks and that their period in the sun may have come to an end.

During the late 1950s and 1960s, politicians and markets convinced themselves that Keynesian fiscal fine tuning could produce a better less volatile world, a view that was ultimately found to be wrong and the consequences of which had to be addressed by the central banks in the 1990s. Since then, we have lived in a world in which it has been assumed that the central banks could eradicate cycles and suppress risk but 2017 may yet turn out to represent the beginning of the end for that particular doctrine – monetary fine tuning may yet go the way of fiscal fine tuning but if that ultimately ushers in an era of stable and conservative monetary policy regimes, we at least will celebrate from a longer-term perspective.

• Important disclaimer information

Please note that much of the content which appears on this page is intended for the use of professional investors only.

Andrew Hunt International Economist London

| « An adviser's guide to AML Compliance | China's High Stakes Tennis Match » |

Special Offers

Comments from our readers

No comments yet

Sign In to add your comment

| Printable version | Email to a friend |