Global Equities: Why it's time to rethink

We are often asked for our view on emerging markets and whether now is a good time to be over or underweight. We feel that the term “emerging markets” is now more a matter of benchmark classification as opposed to some common fundamental reality.

Monday, July 31st 2017, 10:22AM

by Scott Berg

KEY POINTS:

- Emerging market fundamentals are about as dispersed as they have been for two decades. You only need to look at economic growth rates by individual country to see that they cannot be viewed under one singular homogenous banner any more.

- While region and country-level comparisons are important in this new era of emerging market investing, we would also encourage investors to look at sector and industry dispersion when informing a view of change within and across emerging markets.

- While we have high conviction in our emerging market holdings today, if we had to provide one clear and succinct guide to investors seeking to understand emerging markets today, the first step is to ask the question “where is there real change and opportunity?”

We are often asked for our view on emerging markets and whether now is a good time to be over- or underweight emerging markets, given the state of the global economy and how emerging fundamentals are trending. While we always seek to provide a clear and succinct answer, one point we feel is necessary to make is that the term “emerging markets” is now more a matter of benchmark classification as opposed to some common fundamental reality. While perhaps sounding like a subtle distinction, the importance is both high and far-reaching for investors.

Why do we care to address complexity and take the hard road when asked what sounds like a simple question? Because emerging market fundamentals are about as dispersed as they have been for two decades, and this is important. Put another way, the point of maximum fundamental correlation (remember the days of the BRICs ascending as one) was reached some time ago but has now passed, leaving dispersion and opportunity but no lack of confusion in its wake.

Why did this happen? There are many reasons, but most notable is China’s industrialization phase moving on, thus ending the commodity supercycle that, as a byproduct, created high economic correlation between China and major emerging market commodity producers. In addition, the developed world’s growth struggles since 2008 have also muted the secular export theme within the emerging world, leading us to draw a conclusion that emerging market fundamentals have evolved, and evolved for good. Rather than looking back hoping for the good-old correlated times to return, it is important to understand the dimensions of change across and within the emerging world in order to achieve investment success.

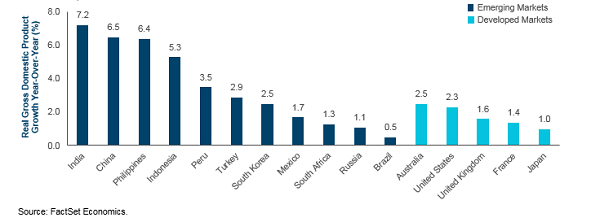

To demonstrate the fundamental dispersion and evolution point, you only need to look at economic growth rates per country (Figure 1) to see that emerging markets cannot be viewed under one singular homogenous banner any more.

Figure 1: Huge dispersion in economic growth levels within emerging markets

As of March 31, 2017

While developed markets share relatively narrow economic growth characteristics (an absence of high growth being the common link), emerging markets offer a breadth of growth backdrops spanning Brazil, with its economy only just getting out of a two-year and very significant recession, to high and very durable growth in India. The fundamental dispersion is further enhanced when you look at other dimensions of what drives short-term and long-term growth rates within countries classified as emerging markets by index providers.

Let’s take Russia and the Philippines as perhaps the most extreme examples. The Russian economy is currently defined by weak economic growth in the near-term (in part given its heavy reliance on energy), weak domestic consumption growth, and a population that is aging at a rate not dissimilar to Japan’s. While energy prices will ebb and flow with the cycle, this is an undeniable long-term headwind. Clearly, however, every controversy and negative data point has the potential to create attractively priced stocks, and Russia’s optical market valuation offers potential value (we would add we do not own any Russian stocks today). But, when rereading the original emerging market thesis, our conclusion is that these are not the fundamentals you were looking for (to use a Star Wars analogy).

By contrast, the Philippines has very little in common with Russia aside from a concession that both are linked by the very broad banner of emerging market “political risk.” This stems from both being led by deeply nationalist and, hence, externally controversial presidents (Putin and Duterte). That’s where the comparison stops, however.

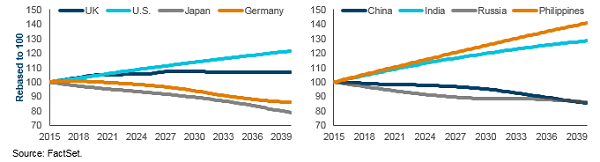

Why? Because the Philippine economy is much less cyclically oriented, given its domestic consumption-oriented growth nature as well as its scarcity of natural resources. The Philippines also has the luxury of being one of the most demographically advantaged economies in the world (Figure 2). This is important because if long-term economic growth potential is indeed a function of productivity growth and working age population growth, as many economic textbooks would imply, then the Philippines has a natural resource (its people) that will stand it in good stead. Regardless, its fundamentals certainly sound a little more like the “emerging markets thesis” of yesteryear, which is also why the market’s valuation is incomparable to Russia, adding another layer of dispersion to consider (as an aside, we are significantly overweight the Philippines).

Figure 2: The emerging markets demographic case has fragmented

Working Age Population Growth Indexed to 100; as of March 31, 2017

The contrasts go on and on. Take Brazil and South Africa and the lack of meaningful structural reform in recent years as political inertia has dominated the need to change with the economic times. Then compare these with India and Indonesia where governments are making real attempts to positively reform, even in the midst of an uncertain global economy.

While India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi has faced challenges and skepticism, structural reform sits at the heart of the rebound in Indian equity prices so far in 2017 (1) as the withdrawal and replacement of large-denomination bank notes, aimed at ensuring the integrity of India’s monetary base, has worked its way through the economy without the “crisis” predicted by many. Indeed, with the process largely complete and with a nationwide tax simplification program about to be implemented as well, India’s loan growth and economic activity looks well set to reaccelerate this year. We have been overweight and adding to our holdings in India, which is composed predominantly of banks and consumer stocks.

This brings us to the point that while the market loves badges—“fragile five” being one, the “BRICs” being another—it’s crucial to distinguish between the complex reality of emerging markets and the catchall summaries used to define the extremes of good and bad. For those wishing further evidence on this point, the change in growth and inflation and the twin deficits of the fragile five (was that really three years ago?) should serve as evidence that no acronym (however catchy) defines a complex reality—long term at least.

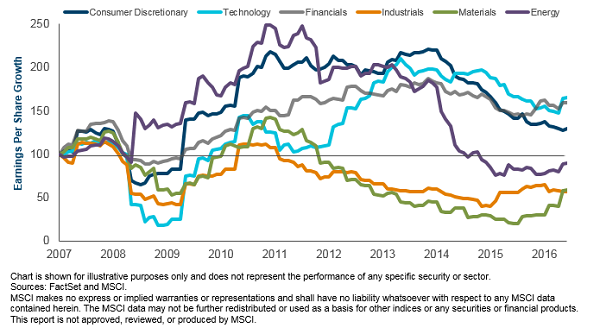

While region and country-level comparisons are important in this new era of emerging market investing, we would also encourage investors to look at sector and industry dispersion when informing a view of change within and across emerging markets. Figure 3 arguably shows the most important aspect of return for emerging market stocks over the medium and long term—corporate profits growth.

The magnitude of dispersion in delivered profits along sector lines is clear and gives some sense of the earnings impairment from the backdrop of commodity price weakness in recent years. While this is a strong fundamental headwind for commodity-oriented stocks, such weakness has been a positive for inflation stability, as well as for corporate profit margins within the emerging world.

Figure 3: The importance of sector and industry dispersion

MSCI EM Sector Earnings Per Share Growth; October 2007–December 2016

Certainly, the end of the commodity supercycle has little impact on the attractiveness of the Indian banking sector, given its domestic roots, and arguably less impact on the Indonesian and Peruvian consumer sectors than macroeconomists observing their commodity-rich economies would want to concede.

The fight between reality versus simplicity centers on the challenges of complexity; this includes a willingness to address what is changing, but, even more so, how to implement a changing view within a portfolio. Getting stock specific in knowledge and implementation is the unavoidable conclusion from our biased perspective, while the extreme alternative is to passively invest in an index that is, by definition, merely a reflection of history.

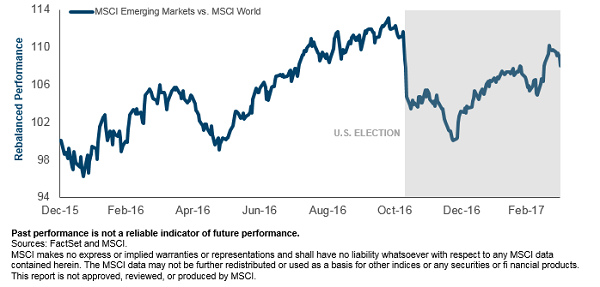

Regardless of fundamental dispersion, one hallmark of emerging market investing that is likely to remain is the higher-than-average volatility characteristics versus developed markets (at least when looking at averages). Without exploring all the details as to the why, the impact of sentiment on emerging markets is nicely demonstrated by the market’s gyrating perspective in light of the U.S. election result (Figure 4), as perceived wisdom has moved from positive for emerging markets (before the U.S. election) to negative (after the election) and back to positive again (year-to-date 2017) (2).

While stock fundamentals never stay still and naturally act as sources of ongoing volatility, our visits to companies in the emerging world (we have visited Mexico City, Lima, Manila, São Paolo, Jakarta, Mumbai, and Beijing in the past year) give us a good sense of what may be changing at both a fundamental micro- and macro-level as we seek to understand what changes in stock prices may be driven by pure noise. From our years of experience, the noise is always likely to be a larger feature of investing in emerging markets, but it is central to the fundamental backdrop of inefficiently priced equity prices within the emerging investment universe.

Figure 4: The topsy-turvy world of emerging markets

As of March 31, 2017

While taxing the nerves, and sometimes the conviction in the short term, this is of course the long-term opportunity for investors. This is borne out when looking at the long-term returns in growth-advantaged segments of the emerging world (by country, industry, and stock) that deliver on their growth promise. While volatility clearly matters, spikes often look small with the benefit of a long-term time horizon. While we feel the stresses of volatility like others, it is often a two-sided coin, with the benefits only able to flow to a portfolio where an investor has the willingness to embrace short-term controversy. The other option is perfect market timing, something we leave to others to execute.

In summary, while we have high conviction in our emerging market holdings and own significantly more than the MSCI AC World Index benchmark, if we had to provide one clear and succinct guide to investors seeking to understand emerging markets today, the first step is to ask the question “where within emerging markets is there change and opportunity?” This is a very different question when compared with “are emerging markets attractive or not”—but it is a crucial first step toward understanding the evolution and change that defines the emerging world today.

(1) The BSE Sensex Index has risen 22.0% year-to-date to June 30, 2017 (U.S. dollar terms).

(2) As of Q1 2017.

Important Information

This material is being furnished for general informational purposes only. The material does not constitute or undertake to give advice of any nature, including fiduciary investment advice, and prospective investors are recommended to seek independent legal, financial and tax advice before making any investment decision. T. Rowe Price group of companies including T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. and/or its affiliates receive revenue from T. Rowe Price investment products and services. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can go down as well as up. Investors may get back less than the amount invested.

The material does not constitute a distribution, an offer, an invitation, a personal or general recommendation or solicitation to sell or buy any securities in any jurisdiction or to conduct any particular investment activity. The material has not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in any jurisdiction.

Information and opinions presented have been obtained or derived from sources believed to be reliable and current; however, we cannot guarantee the sources’ accuracy or completeness. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. The views contained herein are as of the date noted on the material and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price group companies and/or associates. Under no circumstances should the material, in whole or in part, be copied or redistributed without consent from T. Rowe Price.

The material is not intended for use by persons in jurisdictions which prohibit or restrict the distribution of the material and in certain countries the material is provided upon specific request.

It is not intended for distribution to retail investors in any jurisdiction.

New Zealand - For Wholesale Clients only. Not for further distribution.

T. ROWE PRICE, INVEST WITH CONFIDENCE and the Bighorn Sheep design are, collectively and/or apart, trademarks or registered trademarks of T. Rowe Price Group, Inc.

Portfolio Manager, Global Equities

| « Get real! | Investing responsibly: passing the tipping point » |

Special Offers

Comments from our readers

No comments yet

Sign In to add your comment

| Printable version | Email to a friend |