Investors' learned behaviour in need of revision?

Monday, April 3rd 2017, 11:59AM

by Andrew Hunt

We joined the ‘financial world’ in 1987 when inflation had in theory at least been conquered and the Asian Tigers had emerged to become significant parts of the global trading system.

As the years continued, the Asian Tigers were joined within the World Trading System first by the ASEAN nations and then by China and Indochina as the countries climbed the ‘Asian Development Ladder’. Indeed, within 15 years of us starting work, the Asian Region had come to represent around a third of world trade (or more if one included Japan) and importantly companies within the Region had become price-setters in parts of the world trading system.

For historical, cultural, and political reasons, the Asian Region has never been a profit maximising region. Instead, production volume growth was the principle aim of policy and this was primarily achieved through either export growth or import substitution policies, strategies that required a preference for under-valued currencies, heavy levels of state planning in the development process, and persistent corporate financial deficits that were themselves caused by high levels of CAPEX and a long-established tendency not to pass increased production costs on into selling prices. These persistent corporate sector financial deficits were in turn financed by banks at essentially subsidized lending rates, a situation that further implied that households and other savers had to be ‘financially repressed’ (i.er. real interest rates were generally held at very low levels and there was also a severe lack of alternative savings vehicles to the conventional deposits that the banks needed to create - and therefore need people to hold - in order to provide the necessary credit to the corporate and public sectors.

In theory, these non-profit-maximising economies that also did not (really) use the price mechanism to allocate resources should never have been allowed into the GATT / WTO systems, given their model’s basic incompatibility with the Western Mixed / Capitalist systems. However, for geo-political reasons Japan’s rapid re-development in the 1950s had been aided by the West’s sufferance of the under-valued JPY and in the same vein the West also welcomed Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan for reasons that were not solely economic in nature. Moreover, following the fall of the Berlin Wall and an outbreak of hubris amongst Western policymakers, yet more countries in Asia - including of course China’s immense economy - were welcomed into the world trading system despite their theoretical incompatibility.

One must not forget that Chairman Deng’s original industrial strategy for China in the late 1980s was designed simply to achiever one purpose – to raise urban living standards in China through rapid credit and export driven growth but by 1993 it had transpired that Deng’s great leap forward had turned into something of an out of control sprint that had left China notionally a lot wealthier but also saddled with a significant current account deficit that had left the economy with only a few days’ worth of FOREX reserve coverage. There was also an inflation rate that was in excess of 20%.

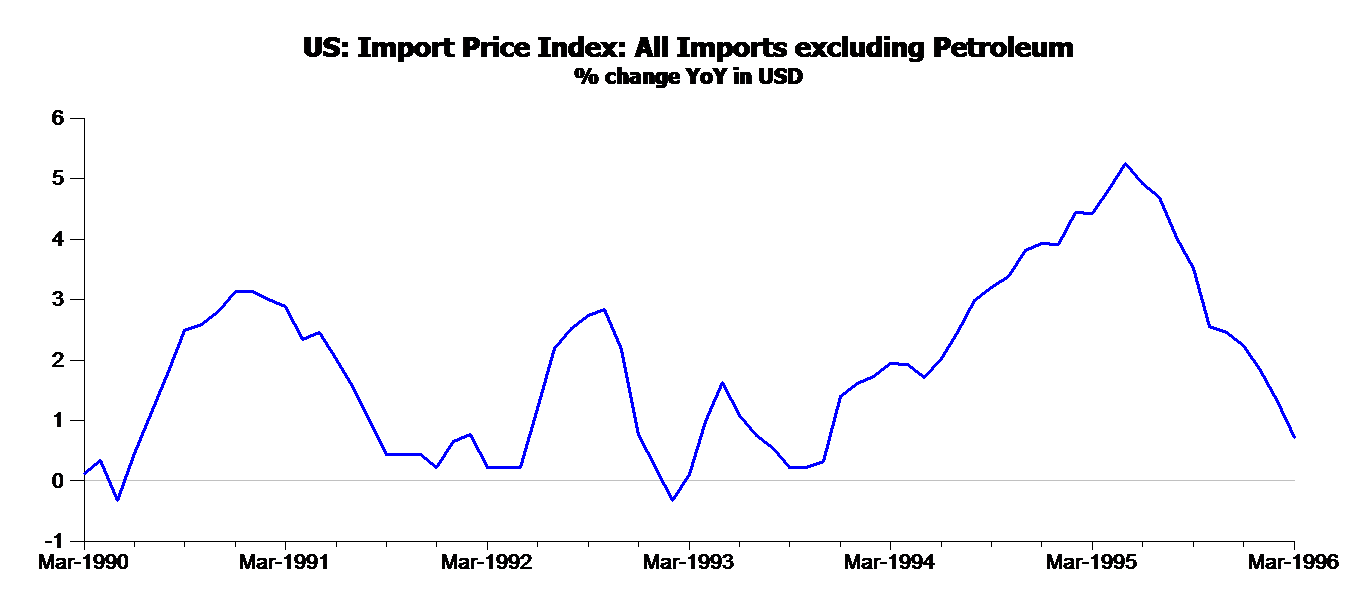

Many investors in the West nevertheless remained infatuated with the ‘China Theme’ and Asian Equity Markets boomed in late 1993, even as global bond markets slowly began to sense that China’s influence on the global system was becoming entirely inflationary. Somewhat belatedly, the FOMC realized that the US was not only overheating internally (albeit only modestly) but that it was also beginning to import inflation and as a result the Fed tightened relatively aggressively during the middle part of 1994. However, the Fed’s tightening, aggressive though it was at the time, turned out only to be quite short-lived phenomenon in terms of its duration. In part, the Fed’s short tightening cycle was the result of the Tequila and Barings’ Crises but it must also be noted that the global inflation threat had appeared to dissipate very quickly in late 1994.

We believe that the rather abrupt end to the global tightening cycle in 1994-5 was caused primarily by the impact on global inflation rates of the Chinese devaluation in mid-1994, the weaker MXP following the Tequila Crisis, the weaker JPY (from June 1995 onwards), and the general ‘collapse’ in Asian export prices over the mid-1990s (despite rising costs within Asia). In fact, by 1997, the dis-inflation in world trade prices had turned to outright deflation as the Asian and then wider GEM Currency Crises unfolded in the late 1990s.

As a result of their increased share of global trade and market penetration, the decline in Asian export prices between 1995 and 1998 was to have a profound impact not just on global inflation rates but also the next 20 years of global economic development.

On average, goods prices account for around a third of a developed-world country’s consumer price index. Therefore, when Asian and hence global export prices were falling at around 3% per annum, they were providing an absolute 100 b.p. of deflation in the Western economies. However, since at this time the Western central banks were aiming to achieve / required to achieve a 2% headline inflation rate, this implied that service sector inflation rates in the West had to be over 4% per annum. This is simply a mathematical reality.

Over 200 years ago, Adam Smith noted that the ‘price’ of an item was determined by the value of its commodity, labour, capital and property inputs. In the case of services, the level of direct commodity input is quite low and in reality the cost of providing a service is dominated by its property and labour inputs. However, the cost of living for most people is dominated by their accommodation costs and hence the ‘living or subsistence wage’ that employers must offer is also a partial function of property costs. Therefore, we can argue that in order to achieve persistent service sector inflation rates, property prices have to rise.

Indeed, against a background of falling import prices, Western central banks had to aim for 4 – 5% rates of service sector inflation in order to hit their 2% headline inflation rate targets. In effect, the persistence of Asian derived deflation implied that the West was required to experience property prices that were rising at faster rates than wages & incomes and this of course implied the need for intense credit booms to lift house prices. These credit booms, and the associated rising tide of property and asset prices, in turn gave rise to the flow-chasing investment styles that have held sway in markets over recent decades.

Moreover, as property and service sector prices rose, so too did the cost of doing business in any given economy (property and service prices being a key cost in any economy) and this made the Western manufacturing sectors ever more uncompetitive. Naturally, growth in the countries therefore had to become more and more concentrated within the service sectors, with all that this implied for income inequality (the service sectors tend to have higher income inequality rates than the goods producing sectors); regional discrepancies (you tend to get regional hot and cool spots within service-driven economies) and slower rates of trend growth (since service sector productivity growth rates tend to be quite low).

Indeed, as a consequence of the implied bias towards the service sectors, the Western economies suffered slower rates of trend growth, higher levels of income inequality, poor levels of housing affordability and high levels of indebtedness relative to incomes. These problems have in turn led to – or at least contributed to - many of the world’s recent political developments.

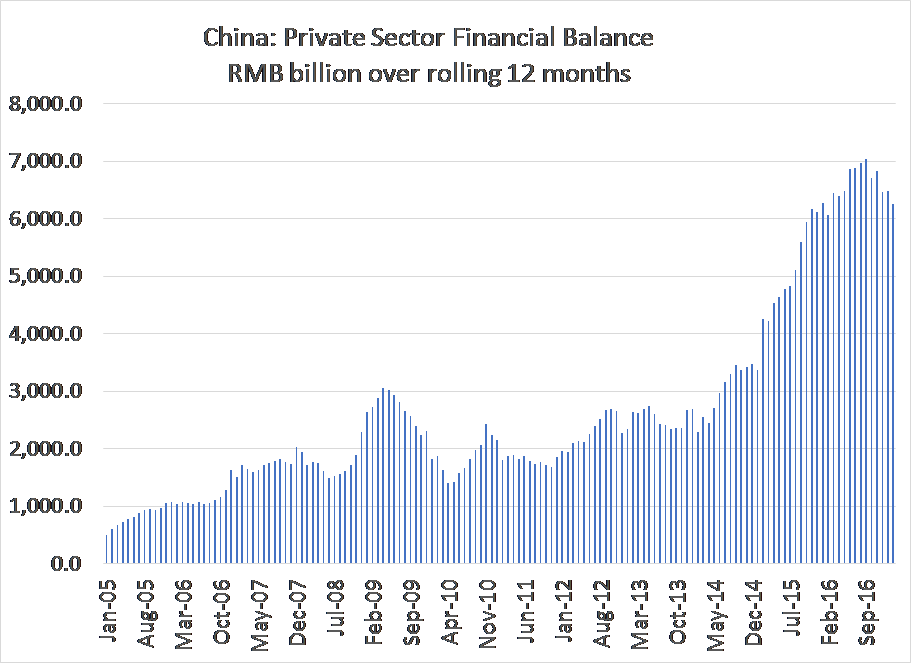

It is however now our central hypothesis that Asia’s savers have reached the end of their willingness to accept financial repression. In Japan, for some time the banks have been losing deposits to cash, Korean households have been looking abroad to escape the country’s low interest rate regime, while in China we find evidence that the authorities’ decision to continue to allow rapid rates of money (supply) growth while at the same time limiting the supply of alternative savings instruments (i.e. alternative to conventional bank deposits) has led China’s households to abruptly lower their savings rates.

The reduction in credit availability in Korea seems to have obliged Korean companies to begin raising their selling prices in an effort to reduce their financial deficits. In Japan, the increased focus on shareholders and the rebound in the Yen have led Japan’s exporters to begin charging higher prices, while the drop within China’s savings rate has clearly created an inflationary boom that has in turn led to the end of China’s export deflation. Crucially, we regard these as likely to be structural rather than cyclical events as the populations’ tolerance for financial repression is tested. Consequently, the West is no longer experiencing finished goods import price deflation.

If we utilise the same mathematical methodology as we employed earlier, then we can suggest that if Asian export price inflation were to reach 3% per annum (for the sake of argument), then service sector inflation rates in the West would be obliged to drop below 1% in order for central banks to achieve their inflation targets. Such a low rate of service sector inflation would likely imply little or no house price inflation (and actually a fall in real house prices).

Of course, over the longer term, this situation would not only imply lower house prices in inflation adjusted terms, it would also imply an improvement in housing affordability. This would probably represent good news for the global economy and much of the world’s population but it would of course be a very different world for investors. Certainly central banks would no longer be chasing wealth effects under this scenario and this might cause more than a few problems for the more speculative end of the housing market spectrum.

Of course, if Asian export prices were to rise at an even faster pace, and OECD import prices were to rise by 10% as a result, then the central banks would only be able to meet their inflation targets if the service sectors were deflating at 5% or so and this would likely entail some significant declines in nominal house prices. Of course, falling house prices within the context of heavily indebted economies would then raise the spectre of Japanese-style balance sheet recessions as the creation of negative equity in the housing market led to higher savings rates and growth-sapping debt deflation. While this might sound a far-fetched forecast, we should note that core (non-oil) import price inflation in the USA in 2007 reached 7.8% with some quite disastrous consequences for house prices.....

We should also note at this point that a sharp rise in import prices can prove highly detrimental to household real incomes, as the US discovered in 2007 (i.e. before the GFC) and as both the US and UK are experiencing today. Certainly, while falling import prices had the ability to lift implied real income growth for the bulk of the West’s population in the late 1990s and 2000s, rising import prices can erode real spending power and create the pre-conditions for stagflation.

Given these various factors, and most importantly of all the simple maths that we have described above, we would argue that if we are correct in the notion that Asia’s economic structure is changing and that on average (i.e. between occasional downward currency adjustments) Asia will tend to export inflation rather than deflation, then the investment world is going to change significantly away from simply chasing flow of funds to having to differentiate between corporate winners and losers in a complex world that is partially obscured by rising general inflation rates.

Indeed, we find it somewhat ironic that just as many of the world’s financial policymakers seem intent on favouring passive / index funds over active fund managers, the need for the latter may finally start to revive. In a world in which central banks needed asset price gains in order to attempt to hit their inflation targets, there was almost always a rising tide of liquidity that could lift all the boats within the investment harbour but if the tide is now about to go out, investors will need to find those companies that are fit enough to make headway against the ebbing tide.

Quite simply, we believe that if Asia is indeed reaching the limits of its financial repression model and that the structure and pricing behaviour of its economy will change with immense implications for the way investors must behave and think over the coming decade – or longer.

Andrew Hunt International Economist

Andrew Hunt International Economist London

| « New Simplicity Investment Funds could save Kiwis $1/2 billion annually in fees | Ready for Bretirement? » |

Special Offers

Comments from our readers

No comments yet

Sign In to add your comment

| Printable version | Email to a friend |