The global economy: weak household incomes constrain outlook

Over the last two months or so, we have travelled quite widely and one factor that has stood out during our travels has been the ongoing and seemingly widespread relative weakness in household income trends.

Monday, August 21st 2017, 10:02AM

by Andrew Hunt

In real disposable terms, US household real income growth is currently running at 1.8%, a moderate but still unimpressive rate that is clearly somewhat slower than that which persisted at this point in 2016. In the UK, household real incomes are falling, as they are in Australia and potentially in Japan. In headline terms, New Zealand is showing respectable real income growth but the data looks rather less impressive in per capita terms. In Germany, household real income growth is proceeding at its now seemingly customary 1.8% rate, which is more than twice the rates being achieved in Italy and Switzerland. Real incomes in France are apparently stationary, while income growth in Canada remains modest and households in aggregate are operating at a profoundly cash-flow negative status. As a consequence, it seems that many of the world’s household sectors may have fallen prey to the curse of much of the British aristocracy in that they are asset rich but cash-flow poor.

This relative lack of income growth has certainly made its presence felt in many recent national elections – the success of "outsiders" in gaining power, or in coming close to gaining power, may have much to do with this weakness in incomes. Moreover, we can assume that this basic lack of consumer “firepower” will continue to act as a dampener on the prospects for the type of sustained global economic acceleration that financial markets appear to be discounting.

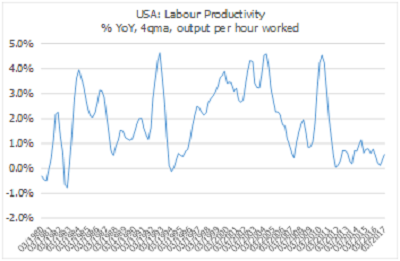

We believe that there are probably two (if not entirely unrelated) factors behind the persistent weakness that is occurring within household income trends. The first is simply the lack of aggregate productivity growth. It would seem that a combination of distorted supply-sides within many of the world’s economies, simple bad luck and an excess concentration on financial rather than ‘real world’ engineering by companies has resulted in weak rates of productivity growth. However, we also believe that in the modern era, a company will not wish to raise the real wages of its staff unless they provide at least an equivalent lift in their level of output per employee.

Secondly, and in a distinct break with the past, the corporate sectors of the US, UK, Japan and Germany now seem obsessed with creating and maintaining financial surpluses so that they can either buy-back their own equity (in the Anglo-Saxon economies) or discharge their existing debts. We well remember a former CIO with whom we worked in the mid-1990s who, when attempting to modernize the Asian offices investment processes, employed a picture showing an ‘Attila the Hun’ type boss who was apparently screaming that “we make money not steel”….

We certainly suspect that the rise of free cash flow analysis, the expanded use of share options to reward managers, and share buy-backs to reward equity holders has led to an enhanced degree of wage discipline within the corporate sector. =Quite simply, the US corporate sector would not have been able to distribute close to $1.5 trillion a year to its equity holders over recent years if it had not kept a tight rein on both wage incomes and fixed capital investment. The latter will, of course, have done little to alleviate the productivity problem.

Although the problem of weak real incomes has undoubtedly worsened over recent quarters, in reality the issue of weak household income trends has been with us for most of the last 20 years. However, during the first 10 – 15 years the problem was obscured – or at least manoeuvred around – via the relatively simple expedient of ‘reforming the credit systems’ in order to allow people to borrow ever larger sums so that they could ignore their income constraints and continue spending (just as the financial sector also used ‘leverage’ to boost returns even as underling income yields declined) but, despite the central banks’ best efforts, this route now seems closed in many places.

Another feature that has made itself all too clear again as we have circled the globe is that despite the faith in and devotion to the concept of wealth effects that is shown by policymakers and investment bankers (on both sides of the revolving door between the two), in practice rising asset prices do not guarantee higher levels of consumer spending. Despite having started my career as an intern for one of the architects of the wealth effect concept back in the mid-1980s, it is now abundantly clear to this author that wealth effects are nothing more than what used to be termed “collateral effects”.

Specifically, we have noted that if asset prices decline relative to debt levels, then the resulting asset liability mismatch may imply that (corporate) borrowers no longer have sufficient collateral in order to sustain their debts, with the result that they will want to – and quite possibly be obliged to – spend less and save more in order to reduce their leverage. This is, of course, quite negative for growth trends within the wider economy. In the case of households, we have long observed that any negative equity that results from falling asset prices (particularly housing) only really matters if it has to be realized by individuals, such as in the unfortunate case of unexpected unemployment or an enforced relocation.

Similarly, when asset prices inflate, it is entirely feasible that some people do feel richer and they may spend more but for those that do not own assets, or wish to own more, then all that higher asset prices may imply is a wealth-sapping higher cost of shelter or a lower expected return on pension assets. We suspect that the ‘net’ result from these two opposing forces is probably quite small.

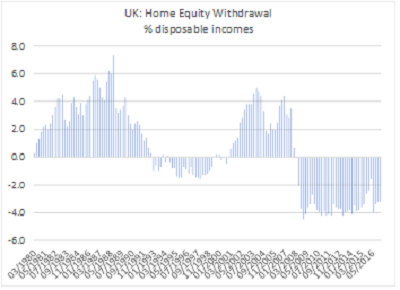

During the 1980s, 1990s and mid-2000s, what higher asset prices did however succeed in doing was to inflate the quantity and value of the collateral that was available to would-be borrowers so that they could trade up the housing market or – crucially – withdraw equity from their homes so that they could finance higher levels of consumption even as their income streams remained unimpressive.

This is, of course, why the central banks’ more recent efforts to recreate the 1990s have largely failed. Since many households are already highly geared and may not wish to borrow more and, more particularly, because banks neither want to return to NINJA mortgages nor have the available capital to do so, higher asset prices have not been able to create another wave of equity withdrawal from the housing markets and its attendant strong rates of PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditure) growth.

Although, in theory, higher asset prices have indeed created more collateral in a world that has become seemingly intent on weaning itself from its former credit dependency, this higher collateral has been immaterial. Of course, politicians have been trained (at least until recently) to believe that higher asset prices boost their popularity while the ex-investment bankers that now dominate many central banks were always likely to have a penchant for inflating asset prices but the truth of the situations seems to be that higher asset prices will only boost consumption if the gains can either be realized (always difficult in aggregate) or more (importantly) used as collateral for further borrowings. During the 2010s, the constraints within the credit system have largely prevented the latter and as a result the much heralded ‘wealth effects’ from higher asset prices have not materialized. Indeed, if these policies had worked in the way that was hoped, US, UK and other household sectors would already be withdrawing equity from their homes rather than struggling as they now find it ever-more expensive to build their own equity stakes…

Instead, all that the higher asset prices have done is to create a division between those that owned the assets that have inflated and those that can no longer afford to acquire assets….. This tension, which carries with it an old vs. young dimension has, as we have already noted, contributed to some of the recent political ‘shocks’ in the West and we very much doubt that these tensions will merely evaporate – unless things change the next round of elections will likely become even more ‘tense’ for the mainstream parties.

At the very least, we would argue that the weak income trends that we noted earlier, and the lack of a ‘functioning’ collateral effect, make it most unlikely that the Western economies will in fact be able to escape their recent disappointing growth trends unless measures are taken to improve underlying real income trends. This hypothesis is of course at odds with the ever-present view in markets that we are ‘on the cusp’ of an economic take-off. but we find it difficult to believe that the global economy can sustain more than a quarter or two of faster expenditure growth without either faster income growth or more credit. Over the last quarter, it does appear that US households borrowed a little more and did a little less home equity building but we doubt that they will be able to sustain this mode of behaviour for more than a few months.

As the Mr Ford–Union Rep dialogue famously noted long ago, companies do have to pay people enough so that they can afford to buy the companies’ wares but this does imply that if the world wants growth and a more equitable society, companies will have to sacrifice profit margins and free cash flow either voluntarily (i.e. by investing in productivity enhancing measures or simply in rewarding their employees) or as a result of state action (i.e. overtly re-distributive policies enacted by governments).

Indeed, if companies choose not to sacrifice their free cash flow voluntarily by investing more, and instead attempt to guard their financial surpluses too aggressively, then we can assume that the next round of general elections will in all probability yield more Corbin-Abe-Obama ‘populist’ measures to actively take money from companies via higher minimum wages or via overtly redistributionist tax policies.

In conclusion, we find that, despite the current wave of ‘global optimism’, households in many of the major economies around the globe remain profoundly income constrained. During the 1990s and 2000s, similar household income constraints on consumer spending were by-passed via a greater use of credit that was itself made possible by an inflation of ‘collateral values’ (these constituted the real ‘wealth effects’ in our view) but in the 2010s this route has been closed by changes within the credit system. As a consequence, we continue to believe that a sustainable acceleration in global growth is unlikely to be sustained for any period of time unless there are first changes within the global system that allow real wages to begin rising, even if this occurs at the expense of the corporate sector’s currently perceived ‘sacred’ level of free cash flow. The most positive way in which the latter might occur would be via a concerted and proactive effort by both companies and policymakers to boost productivity growth levels but the default route, if productivity growth is not raised, will likely come via state-enforced redistributionist policies of the type that were witnessed in the 1970s to such ill-effects.

Andrew Hunt International Economist London

| « Political risk – New Zealand next? | Quantitative investment styles, and when they perform » |

Special Offers

Comments from our readers

No comments yet

Sign In to add your comment

| Printable version | Email to a friend |